The Quebec Writers’ Federation hosted its 17th annual gala on November 18, 2015. Author Adam Leith Gollner opened the ceremony with this remarkable meditation on how a writer seesaws between isolation and community, and on what it means to be a writer, right here, right now.

“…shivering together as readers and as writers…”

“…shivering together as readers and as writers…”

Good evening, everyone. Thank you all for being here. And thank you as well to Lori Schubert and the whole Quebec Writers’ Federation team not just for inviting me to host this evening’s ceremony – but for all the hard work you do behind the scenes, supporting our writing community year in and year out. It’s an honour to be part of this gathering. I’m grateful to have received QWF awards in the past, and I’m thrilled to be able to participate in welcoming this year’s nominees.

One of the shortlisted books that stood out to me this year was Kim Thùy’s Mãn, translated by Sheila Fishman, which is up for the Cole Foundation Prize for Translation. Many of us remember Thùy’s first book, Ru, about her family’s journey from Vietnam to refugee camp to new life in Montreal. There’s a moment in Mãn when a character on a ferry crossing the Mekong has to throw all her ID papers overboard. She realizes that if she wants to survive, she will have to get rid of her identity.

It’s such a vital question here in Montreal, in Quebec, in Canada – the question of identity – for the French majority, for the Anglophone minority, and for all the other cultural communities who have made their lives here. As Mordecai Richler famously said: “Nobody is quite sure what our culture is, or if we even have a national culture at all.”

One of the things that has always struck me about living in this city is the way it can be hard to feel a real sense of belonging here. Many French don’t feel like they belong to this country; many English don’t consider themselves to be a part of this French society; and countless minority groups feel marginalized here as well. Perhaps one quality that connects all of us is that sense of not belonging. It seems to me that there is something quintessentially Montreal about not really fitting in. To be bound together by our outsiderness – to belong by sharing a sense of not belonging – it’s an interesting way of thinking about identity in Montreal. And it’s doubly interesting for this community of writers, which is, after all, made up of people pursuing their craft in isolation.

“It seems to me that there is something quintessentially Montreal about not really fitting in.”

It’s one thing to be a writer who belongs to an invisible community made up of all the writers you have ever loved, but it’s another thing to actually connect with your peers, with those whose work you admire, with talented, smart friends – which is another reason that this gathering is so important.

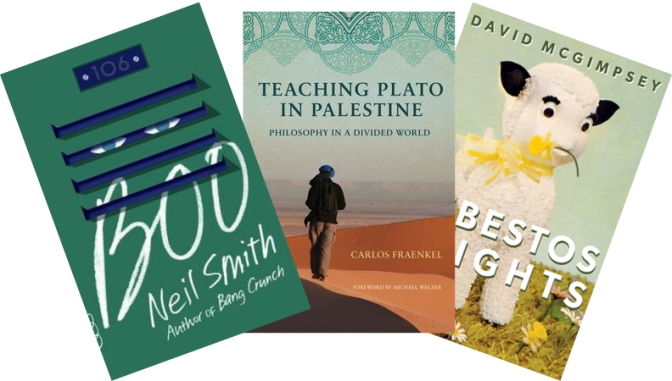

Each year, this event brings the city’s writers together. Every year, I learn about books via the QWF awards that I would have not otherwise known about. New books like Anita Anand’s Swing in the House, about the private lives of modern families just like yours and mine. Or Neil Smith’s Boo, which describes the afterlife in vivid detail, from the perspective of a thirteen-year-old obsessed with evolutionary biology. Or Teaching Plato in Palestine, by Carlos Fraenkel, which suggests that philosophy can provide a way forward in the Middle East. Fraenkel’s thoughts on multiculturalism are fascinating – especially in the context of a mixed-up city like this.

The great Dany Laferrière believes we should all be whoever we want to be – as he explains in his book Je suis un écrivain japonais (I Am a Japanese Writer). What a perfectly Montreal concept: why not be a Japanese writer, even if you are born in Haiti and live in Ahuntsic? He dedicates that book to anyone who has ever wanted to be someone else. All of his books are about his life, and all of his books are about writing. And what he reminds us is that literature can bring us together, it can erase boundaries, it can connect us – no matter how isolated we may feel.

“…why not be a Japanese writer, even if you are born in Haiti and live in Ahuntsic?”

I felt that reading the opening to Kathleen Winter’s Boundless, nominated for the Mavis Gallant Prize for Non-Fiction, which is about her journey through the Northwest Passage. It opens with an epigram by Aaju Peter: “The body is a feather blown across the tundra.”

What a lovely line, I thought, “The body is a feather blown across the tundra.” You can’t really get more isolated than that. But then I realized: I know Aaju! I know the person who wrote that – and I love her. We ate raw seal together in her dining room. She was one of the main people I interviewed while shooting a documentary in Iqaluit last winter. Coming across that passage reminded me again of the fundamental way that books can bring us closer together – and not just in a superficial, I-met-her fanboy sort of way, but in a “we are all feathers blowing across the tundra” sense.

“…literature can bring us together, it can erase boundaries, it can connect us – no matter how isolated we may feel.”

When I read a beautiful passage in one of Heather O’Neill’s books, I feel a sense of belonging. There’s a moment, in the title story of her new collection Daydreams of Angels, when a cherub descends in Montreal during World War II. He goes on a date with a local girl named Yvette, and starts playing the trumpet for her after dinner: “Although impossible to put into words, his melodies sounded most like a baby cooing in its sleep, a girl laughing under the covers, a moan escaping from someone’s lips while making love.”

As readers, we all get to hear that angel’s music – we all get to be part of Heather’s gang. And when I think about the writers I know in this city, no matter how tenuously, I realize that I am part of a community, one that would be far more tenuous if it weren’t for the QWF.

Three of the 2015 QWF award-winning books

Three of the 2015 QWF award-winning books

I think of Taras Grescoe, who lives across the street from me, who helped me get my first book published. I think of Mireille Silcoff, one of my first editors, coming and going between here and Toronto, writing the stories in Chez L’Arabe through her chronic pain. I think of bumping into David Homel at the gym – not nearly often enough, unfortunately. I think of Rawi Hage, always grumbling, always excited to talk about good new restaurants, and always working on his devastating, masterful books. I think of the Filipino novelist Miguel Syjuco, who chose to live in Montreal for the past ten years while writing Ilustrado (winner of the 2010 Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction) and a forthcoming second book. I think of others who created extraordinary things here and continue to do so elsewhere: Anne Carson, Yann Martel, Suroosh Alvi. I think of meetings at cafés with Marianne Ackerman or Anna Leventhal or last year’s Giller Prize-winner Sean Michaels. I think of Ian McGillis at the Gazette, who has done so much to champion this city’s writers. I think of Nisha Coleman, who worked on her new book Busker in a QWF creative non-fiction workshop I had the pleasure of teaching. I think of Geneviève Desrosiers who passed away at 26 having only published one immortal poem in her lifetime: Nous. Us. I think of all the nominees here tonight. I think of so many people: Rodney Saint-Éloi, Julie Doucet, Charles Taylor, Monique Proulx, Dimitri Nasrallah, Benoît Chaput, Louise Penny, Nelly Arcan, Michel Tremblay, Anita Rau Badami, Chris Oliveros, Mark Abley, Carmine Starnino, Saleema Nawaz, Alex Shoumatoff, Lesley Trites, Robbie Dillon, Mikhail Iossel, Michelle Sterling, Ian Ferrier, David Fennario, Nicole Brossard, Leonard Cohen, Mavis Gallant, and of course my mother, Linda Leith.

This is a community, even if it’s diffuse, even if it only coalesces rarely. But this is one of those times. And as we are gathered here, on a beautiful autumn evening, with winter approaching, I think of that unforgettable line in a poem by the young Montreal poet Émile Nelligan, written around 1898:

Ah ! comme la neige a neigé !

What a perfect opening line, here in the country of winter: “Ah! How the snow snowed!” Later in the poem, he too gets into questions of identity: “où-vis-je ? où vais-je?” Where do I live? Where am I going? His answer: “Je suis la nouvelle Norvège.” He was talking about his emotional, psychological state – but also about the fact of living here, in the New Norway, where we’re all trying to make sense of our experience, trying to connect, shivering together as readers and as writers.

A final thought, about où-vis-je, about this country we are part of. Remember our old twenty-dollar bills, the ones with the Haida sculpture on the back? There was a tiny, 6-point font quote there from Gabrielle Roy, who wrote about the part of town we’re in right now, Saint-Henri, in her most celebrated book, Bonheur d’occasion (The Tin Flute). The line that ended up on Canada’s money – on our national currency – says something about who we are, about what it is we value, about this land’s elusive culture. As she put it, and as everyone here can attest: “Could we ever know each other in the slightest without the arts?”

Adam Leith Gollner is the author of The Fruit Hunters and The Book of Immortality. The former Editor in Chief of Vice Magazine, Gollner has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian, The Globe and Mail, Smithsonian, Lucky Peach, and The Paris Review. He lives in the Mile End.

Photos: Via Flickr; no changes made (top); Via Flickr; image edited ($20 bill); Terence Byrnes (headshot)

I love what you wrote, about this non-identity, this sense of not belonging. Or was it about not recognizing our own roots in others. But, sadly, this does not represent only the English Speaking Canadians in Montreal, but mostly all communities in Canada. I am a Quebec French speaking woman living in Toronto. You want to talk about isolated? There are no stores that sell Dany Lafreniere’s book in French in Toronto. There are no french speaking newspapers delivered in Toronto, neither magazines. The two solitudes still exists as strongly in Canada in the 21st century as it did in the 19th. Even more so as the country outside Quebec is trying to blend in with the different poles of the USA. But I must agree with you that the Arts will bring us a sense of what we are. Now that we don’t have to fear a Queen’s portrait in the place of our most avantgardist artists, there is hope that we can get our search of national identity back on the agenda.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful piece. I guess we’re all outsiders trying to work our way in through art.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think this article was most insightful and gave me food for thought. However be assured there is no monopoly on isolation, at least for writers. I have just completed a Memoir, which only became a labour of love after I promised a dying brother to complete it, otherwise I may have pretended I possessed a sense of belonging doing something or connecting with others. Whilst I was writing, isolation wasn’t so much an issue as it has become now it’s completed. What I mean by that is “Will anybody, especially be interested in readying a story about someone without entitlement and with absolutely no sense of belonging? I don’t know. What I do know is that the isolation is scary.

LikeLike

What a beautiful poem about togetherness!

LikeLike

An outstanding piece. Wonderful that someone recognizes this longing in each of us and dares to search it.

LikeLike

“He dedicates that book to anyone who has ever wanted to be someone else. ”

And I have always felt guilty, and been ridiculed, for wanting to be someone else, or rather, to be someone others felt I should not be, perhaps.

Thank you for this lovely article.

Stay Safe,

-Shira

LikeLike